Shannon Wheeler has heard stories of a time when thousands of Snake River salmon passed through the fishing grounds of his Nez Perce ancestors. The fish have been central to the diets, cultures and religions of the Nez Perce and other Pacific Northwestern tribes for centuries.

But salmon runs in the Columbia and Snake River system have declined by more than 90% in the last century, according to estimates from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Oregon Department of Fish and Game, and Wheeler points to 14 federally operated dams as a key cause.

“One of our tributaries last year had eight salmon that we could catch. Eight salmon,” said Wheeler, the vice chair of the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee. “For me, that is something that is not acceptable.”

But it’s these dams that keep third-generation Washington wheat farmer Steve Appel in business. His wheat, along with nearly 30% of the nation’s grain and oilseed exports, is taken up and down the river system through the dams’ locks. Without access to this waterway, he’d have to send it by rail or truck to ports near the coast, which he estimates would more than double his current shipping costs.

“These dams are essential in the current world to keep the farm going,” Appel said.

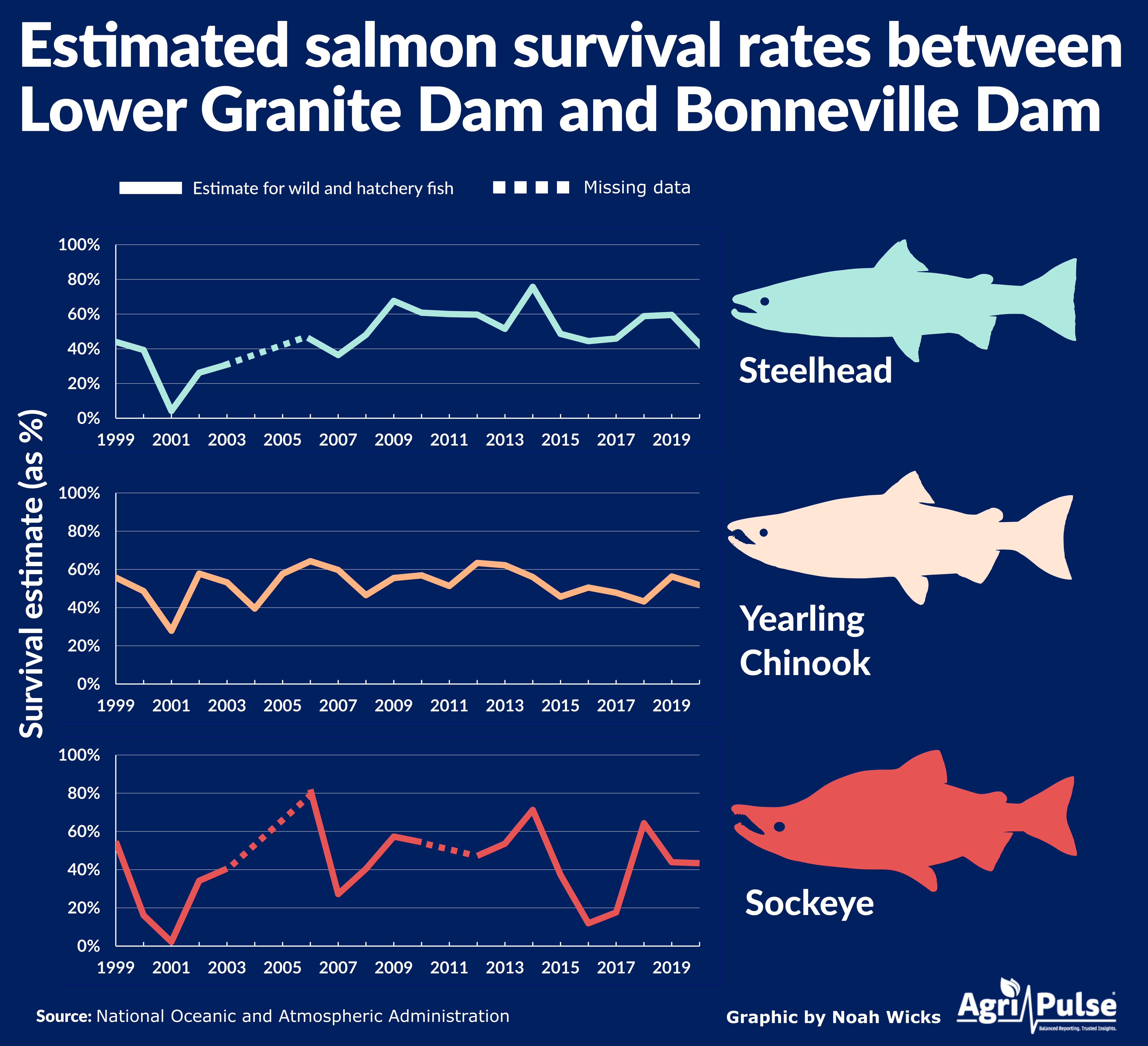

Whether the dams and salmon can successfully coexist has been a point of contention in the region for decades. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recognizes four species native to the Snake River — sockeye, steelhead, fall chinook and spring-summer chinook — as threatened or endangered and, despite recent gains by fall chinook and steelhead, all are hundreds of thousands of fish below their historic population levels.

Federal agencies have poured more than $17 billion into salmon recovery over the last 20 years, hoping to revive populations using fish ladders, diversion screens and hatcheries. But conditions for Snake River sockeye and spring-summer chinook are still dire and, limited on ideas, some federal and regional political actors are starting to look more closely at the possibility of breaching four eastern Washington dams — Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite.

The idea has created rifts in the Pacific Northwest. Calls for breaching the dams from tribes, environmental groups and fishermen have been met with ire from farmers, shippers and utility companies concerned about their livelihoods and the region’s economy.

All sides have a lot at stake. There's no guarantee that breaching these dams will be enough to reverse dwindling salmon numbers, and if they go, grain producers lose an important shipping route, farmers must find other ways to irrigate thousands of acres of farmland, and the region says goodbye to 1,000 megawatts of renewable energy. But if they stay, all four species could continue to decline into extinction.

“It takes this discussion that’s happening in the Pacific Northwest and it’s happening now because it’s going to be us that designs our future,” said Rep. Mike Simpson, R-Idaho, one of breaching’s most vocal defenders in Congress.

Fueling the debate is a 30-year-old series of lawsuits filed by environmentalists, fishermen and tribal governments, including the Nez Perce, that has incrementally edged the dams’ federal caretakers toward more drastic action. In 2017, federal judge Michael Simon ordered the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to spill more water out of the dam, and others have advised the agency to consider dam breaching as an option in its Environmental Impact Statements.

Congress authorized the construction of the dams in the 1960s and early 1970s, granting the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers permission to maintain the dams for navigation, hydropower, recreation and water supply uses. But it did not pass along the authority to breach the dams, which still requires Congressional approval.

Some speculate Simon could order the dams to be breached if an agreement is not reached, though whether a judge could use the Endangered Species Act to exercise authority otherwise held by Congress is legally dubious. The judge wrote in a recent order that it is “premature to consider this issue,” because the parties in the lawsuit have not directly asked him to order breaching or presented a legal argument suggesting he’d be able to do so.

Still, the threat of judicial action has placed pressure on both the Biden administration and members of Congress to come up with a new approach for dealing with the salmon crisis. The White House Council on Environmental Quality and Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., both intend to propose solutions by July 31, the same day the court is set to resume proceedings after temporarily halting them to allow “good faith discussions” to take place among the litigants.

“We would like to see a comprehensive proposal from the executive branch and the legislative branch while we have the litigation pause so that we can actually solve this and do it quickly,” said Todd True, an Earthjustice attorney representing environmental groups in the case.

The legal battle has placed the Biden administration in a precarious position as it tries to juggle fishing rights obligations to tribes, expectations from the courts to implement a lasting solution to salmon declines and concerns from communities about the economic and energy needs of the region. Tasked with maintaining and operating the dams, but limited in their authority, federal agencies have been conducting listening sessions as they attempt to craft an “equitable long-term solution.”

“We cannot continue business as usual,” several CEQ members, including secretaries from the Departments of Energy, the Interior, Commerce, and Defense, wrote in a blog post on March 28. “Doing the right thing for salmon, Tribal Nations, and communities can bring us together. It is time for effective, creative solutions.”

The council’s efforts, however, have drawn concern from eight Republican lawmakers, who worry the Biden administration is focusing too much on breaching the four dams and potentially overstepping its authority in the process.

“These 10 federal agencies, they do not have the authority to change the use of these dams,” Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., told Agri-Pulse. “So I do wonder under what authority they're bringing together these various agencies to explore this drastic and counterproductive measure.”

McMorris Rodgers, a fervent opponent of breaching, has allied herself with Dan Newhouse, R-Wash., Jaime Herrera Butler, R-Wash., and Russ Fulcher, R-Idaho, on the issue. She is pushing the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee to add language to this year’s Water Resources Development Act that would prohibit federal agencies from funding or authorizing studies that consider removing federal dams in the Pacific Northwest.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

“I consider these dams the beating heart of Eastern Washington and the Pacific Northwest,” she said. “Without them, our region, as we know it today, would really cease to exist.”

Murray, on the other hand, announced last October her intention to include a study in the WRDA bill that would analyze breaching’s costs and impacts. She, along with Sens. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., Ron Wyden, D-Ore., Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., and Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, has not yet taken a side on the issue.

Simpson, who represents Idaho’s second district, has crafted his own $33.5 billion plan to breach the Snake River dams, while also allocating money toward building alternate transportation, irrigation and energy sources. The proposal, backed by Earl Blumenauer, D-Ore., also calls for a 35-year moratorium on all litigation related to the dams.

"Everything we do in the Snake River basin, we can do differently if we choose to do it,” Simpson said. “Salmon don't have a choice. They need a river and they don't have one right now."

Breaching does not mean destroying all parts of the concrete dam, but rather, the earthen portion blocking the flow of water down the river. The concrete powerhouses, spillways and navigation locks would likely remain but be entirely inoperable.

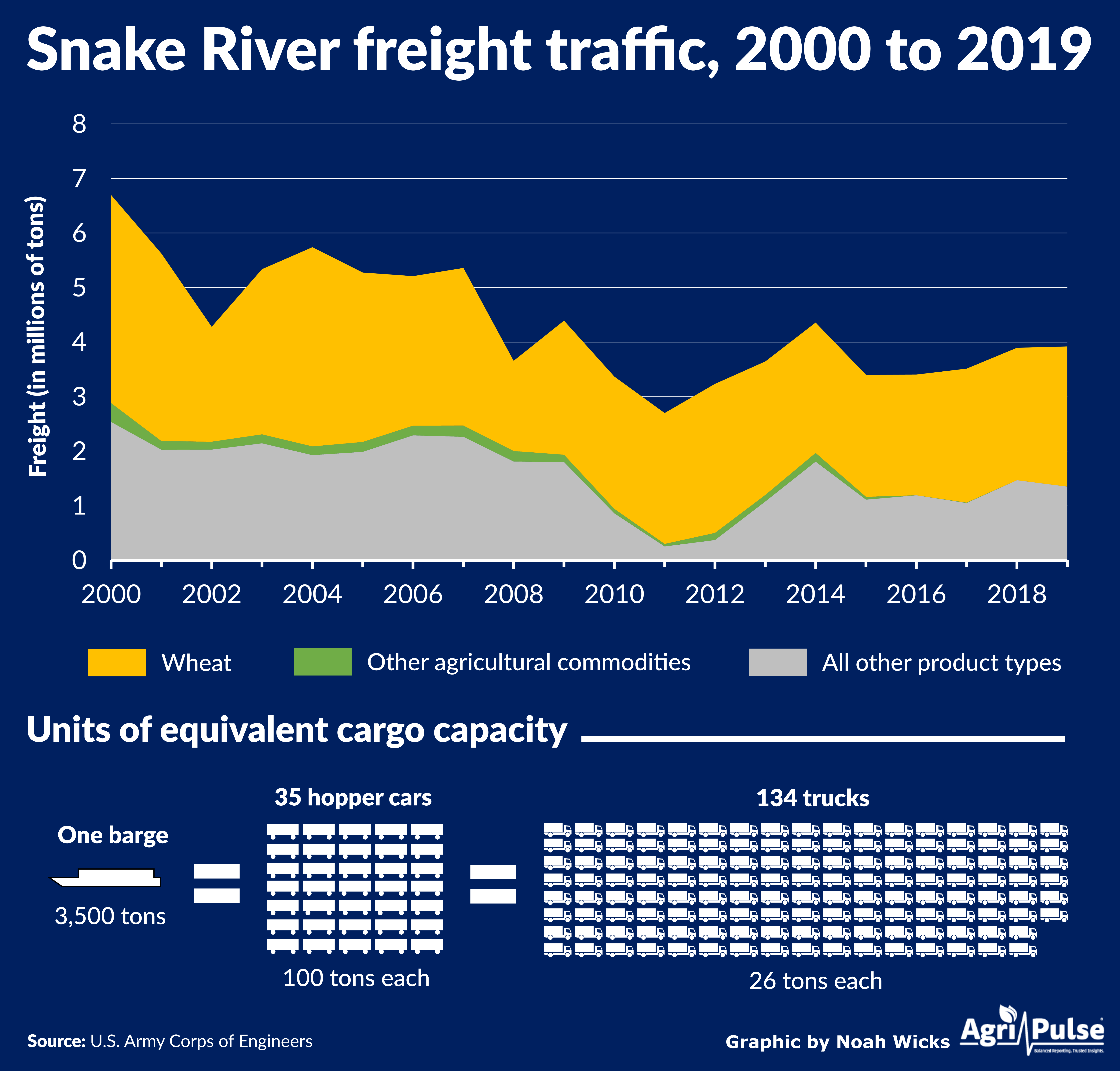

Freeing the river makes barge transportation impossible, which is currently how 90% of the agricultural commodities from the 10-county region surrounding the Snake are moved, according to a study commissioned by the Pacific Northwest Waterways Association. The other 10% are transported by train.

More than $1.1 billion in rail line, bridge and roadway upgrades would be necessary to offset the loss of the navigation locks, PNWA estimates, as the region’s farmers shift to moving 60% of their products by train, 30% by barges further down the river and the rest by truck.

Over 2.5 million tons of wheat flowed through locks on the Snake River in 2020, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Wheat was the most dominant commodity on the river that year, though it has seen a 1-million-ton drop since 2000.

Michelle Hennings, the executive director of the Washington Association of Wheat Growers, said the loss of barging could be devastating for wheat producers in both the Pacific Northwest and other parts of the country.

Midwestern grain is often sent by rail to port cities in Washington or Idaho, where it gets loaded onto barges and sent to the ocean. An estimated 10% of total annual U.S. wheat exports move through the waterway.

That’s part of the reason major agricultural groups like the National Association of Wheat Growers, the American Farm Bureau Association, the National Grain and Feed Association and the National Oilseed Processors Association have publicly expressed their support for keeping the dams.

The toll for farms, according to the PNWA, would be an $18.9 to $38.8 million decline in net cash income per year. Without an increase in federal farm subsidies, at least 1,100 farms in the region could face bankruptcy.

“Some farms might be able to endure this for so long, but the problem is you have small family farms out there and to put this on to them and their bottom line, it could be very detrimental,” Hennings said.

Farmers who rely on irrigation are concerned, too, but unlike the region’s grain growers, many believe the court will order serious changes to the dams. Peeling away from wheat industry groups, the Columbia-Snake River Irrigators Association has proposed a third solution to the salmon problem — lowering water levels around Lower Granite and Little Goose dams.

A two-dam drawdown would keep the dams intact and allow irrigators to continue pumping water on 90,000 acres of land near the Ice Harbor dam. It won’t allow for barges to pass those two dams, though CSRIA board representative Daryll Olsen believes it to be a better solution for farmers than dam breaching.

“We know that there's going to be something that's going to take place,” Olsen said. “We're not presumptive enough to say what it is, but we certainly want to be part of trying to sculpt what the possibilities are and you don't get there by just pounding the table.”

But, for right now, the dams are still standing and will remain operational for the foreseeable future. A longtime court case has rolled to a temporary halt, several members of Congress remain on the fence, and federal agencies haven't given a clear indication of what path — if any — they plan to take to restore salmon populations.

The decades-long search for a solution, it appears, will come to a head in July.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.