The Biden administration, in a bid to expand U.S. wheat acres to offset Ukraine’s export losses, wants to make more farmers eligible for insurance when they grow wheat and soybeans in the same crop year. But some industry experts doubt the plan will do as much to scale up wheat production as the White House hopes.

Farmers who double-crop, or directly follow one crop with another, face tighter time constraints than they do just growing a single crop. The practice almost always results in reduced yields for both crops, though the combined acreage of both can be enough to counteract that loss, in the right circumstances.

President Joe Biden's plan centers on increasing the number of counties that allow farmers to insure double-cropped fields. Only a limited number of counties can be added, however, since the Agriculture Department is required to keep crop insurance actuarially sound and only certain regions have environmental conditions suitable for the practice.

Concern over an expected increase in global hunger rates stemming from the war in Ukraine has government officials and lawmakers scrambling for ways to increase wheat yields in the near term. Biden, in a visit to an Illinois farm on May 11, made it clear that he was willing to soften rigid crop insurance rules surrounding double-cropping to support more farmers as they tried out the practice.

President Joe Biden

President Joe Biden

“Double-cropping comes with some real risks,” Biden said in his speech that day. “The growing season for wheat is short and if the weather conditions aren’t ideal, or aren’t at least good, or there are other disruptions, then the timing of everything is thrown off. But it’s a risk we need to take.”

In a double-cropped rotation, winter wheat is typically planted in the fall and harvested in late May or throughout the summer. The success producers see with double-cropping stems from when they can plant their soybeans, typically a higher-earning crop, according to Greg Halich, an associate extension professor of agricultural economics at the University of Kentucky.

“On an average year, as you delay soybean planting, your yields are going to go down,” Halich said.

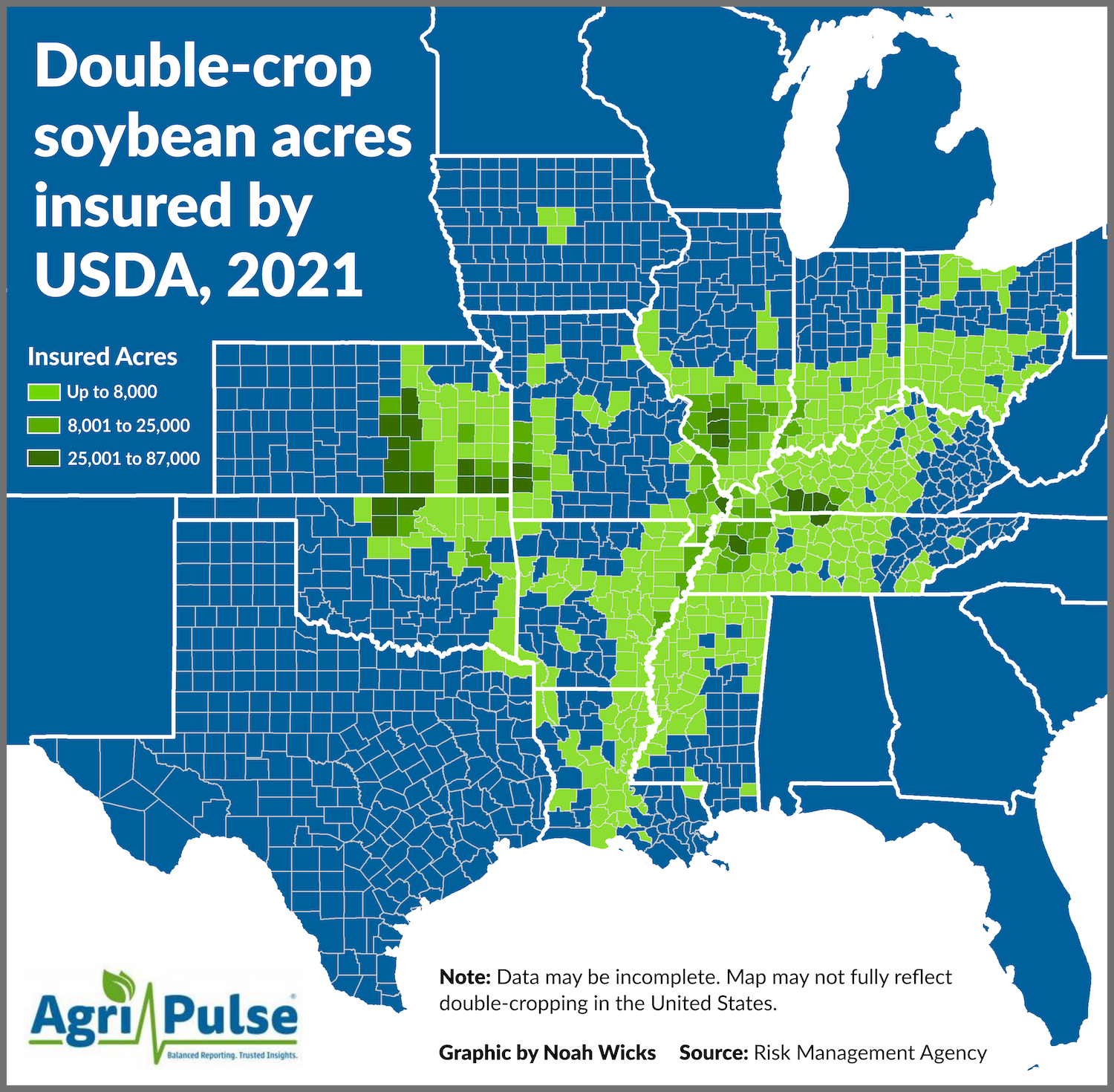

Due to the unreliability of the practice. there are only 1,254 counties where farmers are allowed to insure their double-cropped acres. The counties are located in areas where the growing season is long enough to offer farmers a chance for success with double cropping.

“You don’t want to be issuing insurance policies that will trigger indemnities on a crop that wouldn’t produce," said Jonathan Coppess, an assistant professor of agricultural and consumer economics and the director of the Gardner Agriculture Policy Program at the University of Illinois. “It would be like insuring a car you know you’re going to wreck.”

Over 2.5 million acres of double-crop soybeans were insured in 2021, according to USDA data, though these acres may not have all been planted with wheat. Kansas was home to 609,000 acres, the highest amount of any state. Illinois followed with 396,000, while Kentucky had 380,000 and Missouri had 284,000.

Farmers who don’t live in counties that allow cover cropping can still insure their cover-cropped acres, but only if they are able to secure a written agreement allowing them to do so. Andrew Larson, the director of market development for the Illinois Soybean Association, said many aren’t even aware that this is an option or have trouble providing some of the necessary information, if they have not insured their double-crop acres in the past.

“Written agreements have required ... production history background, and sometimes it’s very hard to establish that if that data has not been collected,” Larson said. “Sometimes, FSA information is helpful to help fill that in, but sometimes the FSA data is not completely accurate.”

Biden, in his push to increase double-cropping, wants to add as many as 681 counties to the list of those approved to insure double-cropped acres. Many of the additional counties are likely to be in Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky and Alabama, said Chandler Goule, CEO of the National Association of Wheat Growers.

But the additional acreage likely will not be enough to make up Ukraine’s wheat losses, Goule said. Even if wheat were to be planted in a double-crop rotation with every acre of soy grown in those four states, NAWG estimates it would only replace around 25% of the wheat that should have been exported from Ukraine, falling short of the administration’s goal of replacing at least 50% of the lost exports.

“I think, in theory, it’s a good idea,” Goule said. “But we need to look at something that is going to work for a larger swath of where wheat is actually grown.”

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

Biden also proposed a $10-per-acre double-cropping insurance incentive, but the idea went nowhere in Congress.

Gary Schnitkey, an agricultural economist at the University of Illinois, said the current market prices for both wheat and soybeans should be a bigger motivator for farmers to double-crop than the $10-per-acre payment would have been. He expects to see use of the practice increase in the areas where many farmers already double crop. He said farmers outside of these areas would be more hesitant since many don’t currently raise wheat.

“If you look at budgets right now, wheat, double-crop soybeans would be projected to be more profitable than either corn or soybeans in most parts of the Midwest where it can be grown,” Schnitkey said. “So there likely will be more of it going into 2022, given that prices hold from now until fall.”

Jeff O’Connor, the farmer Biden visited when he gave his May 11 speech, said he believes the administration’s planned work on crop insurance would help reduce some of the obstacles currently standing in the way of farmers planting wheat. O’Connor usually raises 100 acres of wheat on his 800-acre farm.

“It's a significant investment, so to try to talk to farmers that have not raised wheat in the last 20 years and get them interested in it, and without any real history themselves of double crop, it's a formidable barrier,” O’Connor said. “I know they’re hoping that this removes some of those barriers.”

The Biden administration has floated other ideas as well, like offsetting prevent-plant penalties, which restrict farmers to receiving only 35% of their prevented-planting indemnity if they plant a second crop on the same land that year, or treating winter wheat plantings like cover crops in USDA conservation programs.

But there are limits to what the administration can do on its own without additional legal authority, Coppess said. He said Congress would likely have to weigh in on larger decisions, like allowing double-cropped cash crops to be treated like cover crops in USDA programs.

For more news, go to www.agri-pulse.com.