A San Joaquin Valley lawmaker has been hoping to modernize water management in California by dissolving the State Water Resources Control Board. While a policy committee quickly struck down the provision to dismantle the board, the bill rekindled a growing interest among urban lawmakers to overhaul the water rights system in response to drought, climate change and environmental justice goals.

Senator Melissa Hurtado of Sanger introduced the measure, Senate Bill 1219, soon after the launch of the new Select Committee on Human Security. With Hurtado as chair, the committee hosted a lengthy informational hearing in December on the crisis unfolding in the valley’s farming communities as the drought deepens and diminishes paychecks along with local economies.

“Water security is not just about the Central Valley. It's not just a California issue. It's a global issue,” said Hurtado, when introducing SB 1219 during a Senate Natural Resources and Water Committee hearing last week. “Report after report tells us that water scarcity needs to be looked at in a nexus framework, with food, health, energy and security a part of it.”

She cited findings from a 2012 national intelligence report that water scarcity is posing a risk to global food markets. Terrorists, she argued, could use water as political leverage against countries and investors.

Hurtado was juggling two hearings at once, arguing for modernizing the water system through separate measures. Just minutes earlier, the Senate Governmental Organization Committee debated her bill on cybersecurity for water infrastructure. In both hearings, Hurtado said California’s food and water sectors stand vulnerable to cyberattacks and that the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office has concluded the state’s critical infrastructure is not prepared for the rising frequency of attacks.

Yet SB 1219 focuses on protecting communities and agriculture instead from state agencies leveraging regulatory authorities to control water flows. The measure describes the water board as outdated and failing to manage water adequately for future generations, acting instead as a “bureaucratic barrier” for many Californians in seeking access to water. Hurtado stressed that 24 state entities govern water in California.

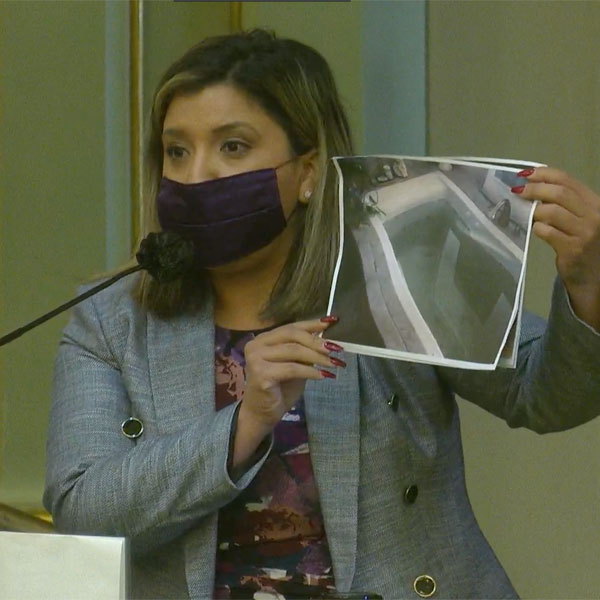

Sen. Melissa Hurtado, D-Sanger, in 2021 displays a photo of a bathtub a constituent filled for drinking water.

Sen. Melissa Hurtado, D-Sanger, in 2021 displays a photo of a bathtub a constituent filled for drinking water.

“Imagine disadvantaged communities having to deal with trying to get clean water and having to navigate all these different entities,” she said, adding that staffing issues at the board have led to ongoing fee increases for stakeholders.

“It's laborious. It takes years longer than you've been in the Senate,” Taylor told the lawmakers. “Communities like mine are dying on the vine. We need help.”

Frank Galaviz, a resident of Teviston in Tulare County, shared his experience with running out of water when the town’s pump broke last year, with “no water to bathe the children in, wash clothes, brush our teeth and flush the toilets.”

SB 1219 would have established a blue ribbon commission composed of various cabinet members and charged them with developing a new system that would prioritize preservation and long-term sustainability. The responsibilities of the water board would shift to the Department of Water Resources (DWR).

A policy analyst for the Senate committee, however, found it unlikely that such a commission would agree to dissolving the board. His report to the committee acknowledged the statutes and laws governing water resources date back to the founding of the state and were formed “somewhat haphazardly,” with a patchwork of local governments mixed with investor-owned water companies.

“Most of these were formed in a different era, with a smaller state population, different public priorities, and different problems,” according to the report.

The bill’s opponents agreed that California needs to reform its water management system but argued the state must instead review the “deeply inequitable and unsustainable water rights system.” Doug Obegi, an attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), was concerned that the bill would delay much-needed reforms to water rights and create conflicts of interest in granting authority over water rights to DWR, when the agency itself holds a water rights permit for operating the State Water Project.

Looking for the best, most comprehensive and balanced news source in agriculture? Our Agri-Pulse editors don't miss a beat! Sign up for a free month-long subscription.

He seized on arguments made by Uriel Saldivar, a senior policy advocate for Community Water Center, an environmental justice nonprofit co-founded by water board member Laurel Firestone. Both advocates said DWR is not equipped to handle the board’s programs and lacks a transparent governing board that incorporates public participation.

Several environmental groups registered opposition to the bill; no groups were listed in support.

The hearing marked the second time for Sen. Henry Stern of Canoga Park, in his new role as committee chair, to side with NRDC in opposing a measure on water management. In March the committee voted down legislation for establishing a funding account for water storage and conveyance projects. The skepticism over funding water projects has not been forgotten by Hurtado, who said SB 1219 and her previous bills to fund conveyance canal repairs show her persistence “in fighting back misinformation.”

“We must work tirelessly to find solutions to protect our water, which by default will protect our food supply chain,” she said.

Hurtado accepted committee amendments on the bill to clarify some of the language but pleaded with the committee to not strike out the provision dissolving the water board out of concern for weakening the bill.

“My district in California needs real change,” she said, adding that’s what this provision would give them.

Stern countered that along with the potential conflict of interest, “major equity and biological integrity issues” in the bill would present challenges in protecting ecosystems in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Bay–Delta. He championed further amendments to change the commission to a committee and broaden its scope to encompass more resource management decisions, such as flood control and land use planning, and to deliver a set of recommendations on updating water laws and regulations.

“When it comes to the politics of water and our legislative solutions, the water board is always an easy target,” said Stern. “As someone who has family in agriculture and farming and ranching, I know that's the common gripe.”

He emphasized that the state must maintain environmental justice to disadvantaged communities if the legislation were to pass.

Sen. John Laird of Santa Cruz pointed out that if he were still leading the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA), this bill would transfer the water board’s authority to him. During his tenure in former Gov. Jerry Brown’s administration, Laird advocated for returning the state’s waste management board to CalEPA just months after legislation signed by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger dissolved the board and shifted its authority to CNRA.

Laird defended the water board and its implementation of the state’s clean drinking water program. The board took over administration of the program a few years ago to “get money out the door” more quickly for grant funding, according to Laird.

“What's at the root of this is the very difficult question that people have rights to more water in California than exists,” said Laird, adding that the water board has “the obligation to mediate that situation.”

He applauded Australia for revamping its water rights system after a nine-year drought, reappropriating water across agriculture, municipalities and the environment.

“We have an antiquated system that doesn't give rights to people in a way that they want to conserve,” he said, suggesting that agricultural interests take more than is available for the environment. “We should stand back from just assuming that blowing up an agency is the answer to all our concerns.”

Farm groups were silent on SB 1219 but opposed Hurtado’s bill on reporting cyberattacks over concerns about how it would work with California’s diversity of farms and ranches. Hurtado had amended the bill to change the reporting from mandatory to voluntary to assuage some of those concerns. That bill passed committee with Democrats in favor and Republicans abstaining.

The water board is at the center of a separate piece of legislation that passed committee last week. Assembly Bill 2639 would require the board to adopt a final Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan before 2024 and to incentivize the board to move more quickly, it would prohibit the board from approving any new water right permits for storage projects until the plan was approved—potentially stalling the proposed Sites Reservoir Project.

The measure builds on a recent report from a handful of California law professors and former state officials recommending updates to the state’s water laws to address drought and climate change.

While opponents of SB 1219 said that a drought crisis is not the time to overhaul water management, proponents of AB 2639 argued the drought is driving the urgent need to update water quality standards to protect native fish species in the Delta watershed.

“The lack of modern water quality standards also hurts long-term planning for water projects by creating uncertainty,” argued Assemblymember Bill Quirk of Hayward, when introducing AB 2639.

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.