The Agriculture Department’s tracking of foreign land ownership relies heavily on investors to voluntarily report acquisitions, and enforcement cases have dropped dramatically even as the number of transactions has surged over the past decade, according to an Agri-Pulse analysis of USDA data.

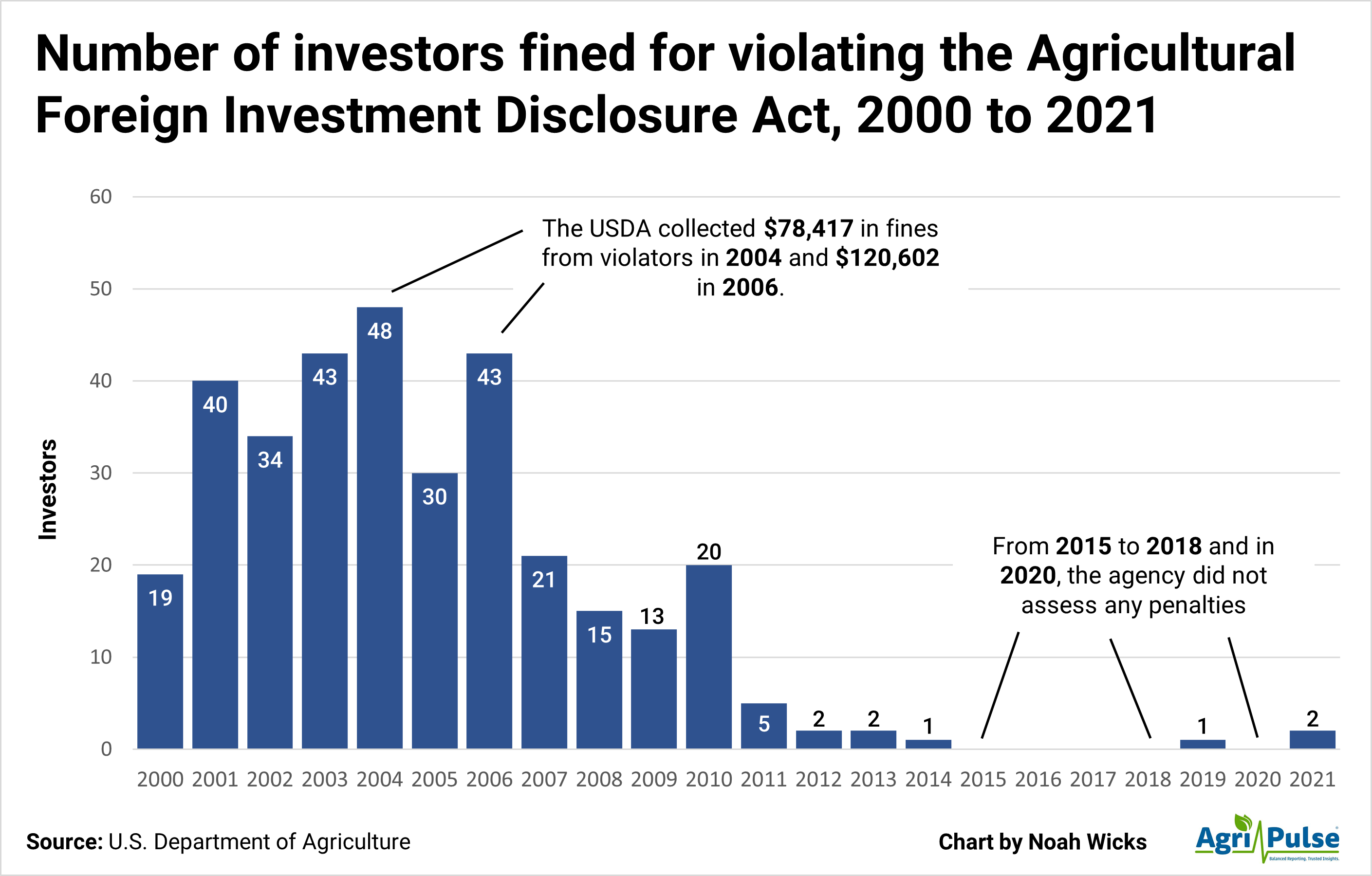

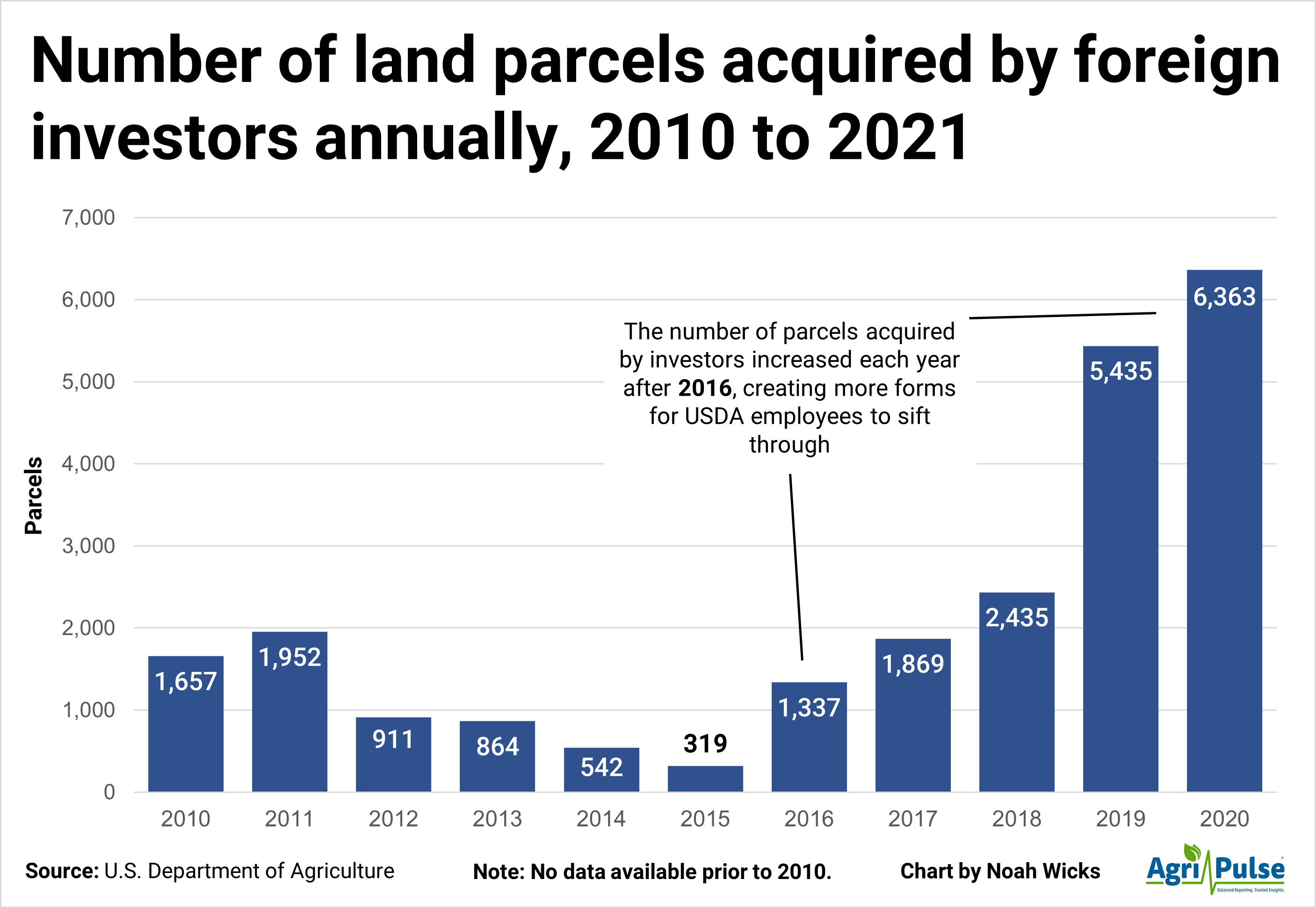

USDA has assessed just eight penalties since 2012, totaling $245,818, and only three of those have been imposed since 2015, including $135,000 in fines levied against a pair of Chinese firms last year in connection to investments in Texas. Meanwhile, the number of foreign acquisitions reported to USDA jumped from just 911 parcels involving 186 investors in 2012 to 6,363 parcels purchased by a total of 323 investors in 2021.

By comparison, USDA reported $870,000 in fines against 331 investors from 2000 to 2011, according to the data obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

It's not clear from the data whether the drop in enforcement cases is due to increased compliance by investors. A USDA official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said it could be a combination of that and a shift in agency priorities. The official said Farm Service Agency employees focus on informing investors about the reporting requirements and compiling the information that is submitted rather than on imposing penalties that could disincentivize filing.

"Our goal is not to penalize them. It’s to get the information," the official said. "We don’t have an investigatory arm. We’re not going out and trying to seek out people who may or may not be reporting.”

Some 27.6 million acres of foreign-held land have been reported to FSA since the Agricultural Foreign Investment Disclosure Act was enacted in 1978. Most of the companies found in violation turned themselves in; USDA has a staff of just three people to oversee the reporting law, and officials acknowledge that some transactions likely go unreported.

“We can’t just go out and stop at every farm and ask about the ownership,” Farm Service Agency Administrator Zach Ducheneaux told Agri-Pulse.

Brazos Highland Properties, a wind energy company with ties to Chinese Communist Party member Sun Guangxin, was hit with a $120,000 fine in 2021 after the company failed to register 102,000 acres of Texas land with the USDA within 90 days of the transaction. It is the largest penalty paid by any of the violators to date.

Harvest Texas LLC, another Chinese company affiliated with Guangxin, was also assessed a $15,019 fine last year for not reporting its purchase of 29,704 acres of land in Texas.

RMK Select Timberland Investments, a Denmark-based company, was subject to the second largest fine, paying $111,000 in 2011. The Walton Group, a real estate investment firm with clients from a variety of countries, followed with a $74,000 fine it paid in 2013.

The law requires foreign investors to file a form with the Farm Service Agency in the county where land is purchased, detailing the number of acres acquired, the buyers' country of origin, the purchase price, and the intended use of the land.

“When you buy it, sell it, or change your status as a foreigner relative to that parcel of land, each of those changes require a filing,” said Marisa Bocci, a real estate lawyer that specializes in farmland and agribusiness transactions.

Foreign investors who fail to report their land purchases within 90 days can incur a late fee worth 0.1% of the land's value for each week purchases go unreported, with the penalty capped at 25% of the land's value. Investors who file false or misleading information can be fined up to 25% of the land value.

AFIDA was intentionally designed to give investors the responsibility of reporting their landownings to the USDA, rather than making the agency track them down. Sen. Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican who was one of the law’s original sponsors, said Congress didn't want to overburden FSA offices.

“That’s the way we had to write it,” he told Agri-Pulse. “You’ve got to remember though, there are penalties in there for not reporting, and I guess in America we assume laws are going to be followed. If you don’t follow them, there’s consequences.”

Rumors of mass foreign land purchases in the 1970s had led to congressional debates over whether foreign investors should be banned from buying farmland. Congress asked the Government Accountability Office and federal agencies to gather numbers on foreign land ownership, but all concluded the data they needed just didn’t exist.

Interested in more coverage and insights? Receive a free month of Agri-Pulse!

Congress commissioned a study in 1978 to determine the feasibility of creating a system for tracking foreign ownership of farmland. The report, according to congressional records, would have analyzed the tracking methods used in other countries, how public title and tax records could be used and what other public and private information sources existed.

The study was slated to be finished by the fall of 1979. But lawmakers introduced AFIDA before it was completed, even though USDA officials advised them to wait.

“I have not seen any bill before this committee that would resolve the problem that you are talking about,” USDA economist Howard Hjort told lawmakers at a 1978 hearing. “If it is true that we do not know how to precisely identify foreign ownership — which it is — then there has to be a study to do that. Simply getting information on registration is not going to resolve that problem.”

The USDA official who spoke on condition of anonymity told Agri-Pulse that FSA occasionally hears of foreign land purchases that haven't been reported to the agency and will send a letter to the buyers informing them of a potential violation.

The official also said county FSA offices find it more difficult to spot potential violations than they did in previous years, due to the changing nature of transactions and their complexity. AFIDA requires reporting to the third tier of ownership, so any company that owns a company that owns a company that holds agricultural land has a responsibility to report.

USDA has the power to reduce the penalties it assesses — and often does — to encourage investors to come forward if they miss a filing, the official said. The agency can decrease the payment based on the duration of the violation, the method of discovery, extenuating circumstances and the nature of the misstated or missing information.

The USDA official said most of the penalties the agencies have assessed have been “modest” since the entities generally are quick to provide their information once they become aware they are in violation of the law. Widespread use of large penalties could discourage investors from filing late, they said.

“We want to avoid this result,” the official said. “It is a balancing act and the ultimate goal is to maximize compliance with the law.”

Kenneth Ackerman, a lawyer and former USDA official who represented Brazos Highland Properties in its discussions with the agency, said the Texas law firms the Chinese company worked with did not file the AFIDA forms when they were preparing the rest of the paperwork needed for the transactions.

The wind energy company's purchase of Val Verde County farmland garnered controversy in 2017 and 2018 due to its close proximity to a military base. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, which reviews certain land transactions for potential national security risks, eventually cleared the transaction.

Brazos later became aware that it had not filed the correct paperwork with FSA and submitted the forms after meeting with the agency to discuss the situation, Ackerman said.

After weighing the circumstances, the agency lowered the original $21 million fine to $120,000, according to a letter it sent to Brazos.

“We felt that it was a fair fine, recognizing the fact that we had been remiss in not filing the forms on time,” Ackerman said.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have proposed changes to AFIDA after expressing concerns about the effectiveness of the law and the accuracy of the current numbers.

Sens. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., and Tommy Tuberville, R-Ala., have proposed requiring that fines be at least 10% of the fair market value of the land, while Rep. Mark Pocan, D-Wis., suggested eliminating the 25% cap on penalties.

“We just want to make sure we're accurately collecting this information on a regular basis so that we have an idea if there's a real problem or not,” Pocan told Agri-Pulse. “We want to make sure that USDA is getting and analyzing the information needed. If they need resources, we’re more than glad to help them.”

Other lawmakers are taking aim at increasing USDA's transparency and enforcement. Grassley and Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., introduced a bill in July requiring the USDA to publish every AFIDA filing in a searchable online database. Twenty-one Republican House members also wrote to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack with questions about the agency’s methods for ensuring AFIDA compliance.

The agency is looking internally at how it can improve its data collection efforts. The USDA source said the department is evaluating its penalty structure for late and erroneous filing, increasing outreach to stakeholders who have a role in foreign transactions and modernizing the way it collects and disseminates the underlying data.

“We're doing everything that we're asked to do with regard to documenting foreign ownership of agricultural land,” Ducheneaux said. “If more is asked of us, we'll try to find a way to do it.”

For more news, go to www.Agri-Pulse.com.