As term limits expire in the coming years, a wave of new lawmakers and their staff will flood the Capitol. The newest part-time residents of Sacramento will undoubtedly visit the historic district, which was ground zero for the great flood of 1862. That sleeping disaster, scientists suspect, is set to reawaken as the state swings wildly from extreme drought to floods. Under such a megastorm, the city would surrender to its two rivers and submerge within a massive floodplain. One of the world’s most productive farming regions would be wiped out in just days.

“A modern-day repeat would be disastrous for California, which has 40 million people instead of the 400,000 or so who were here during the last big one,” said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, and science fellow at The Nature Conservancy. “There's about a 50/50 risk of an 1862-level event in the next 40 years.”

The Category 5 storm that deluged California in October and broke a 24-hour rainfall record for Sacramento indicates such megastorms are now a reality for California, while the Pacific Northwest and several other regions in the world have already suffered extreme flooding this year. Speaking at the California Water Policy Conference last week, Swain described the state as fortunate for experiencing such a storm at a time when reservoirs were low and soils were parched from drought, rather than midwinter after other atmospheric rivers.

“Sacramento is actually a poster child for the kind of dramatic statistics from the past year,” said Swain, in describing a whiplash effect from the state becoming both wetter and drier under climate change.

Under this “climate complexity,” California is not losing water overall, but precipitation is becoming concentrated into more intense winter storms, followed by unprecedented evaporation from warmer springs and an even more intense dry season that is expanding further into fall.

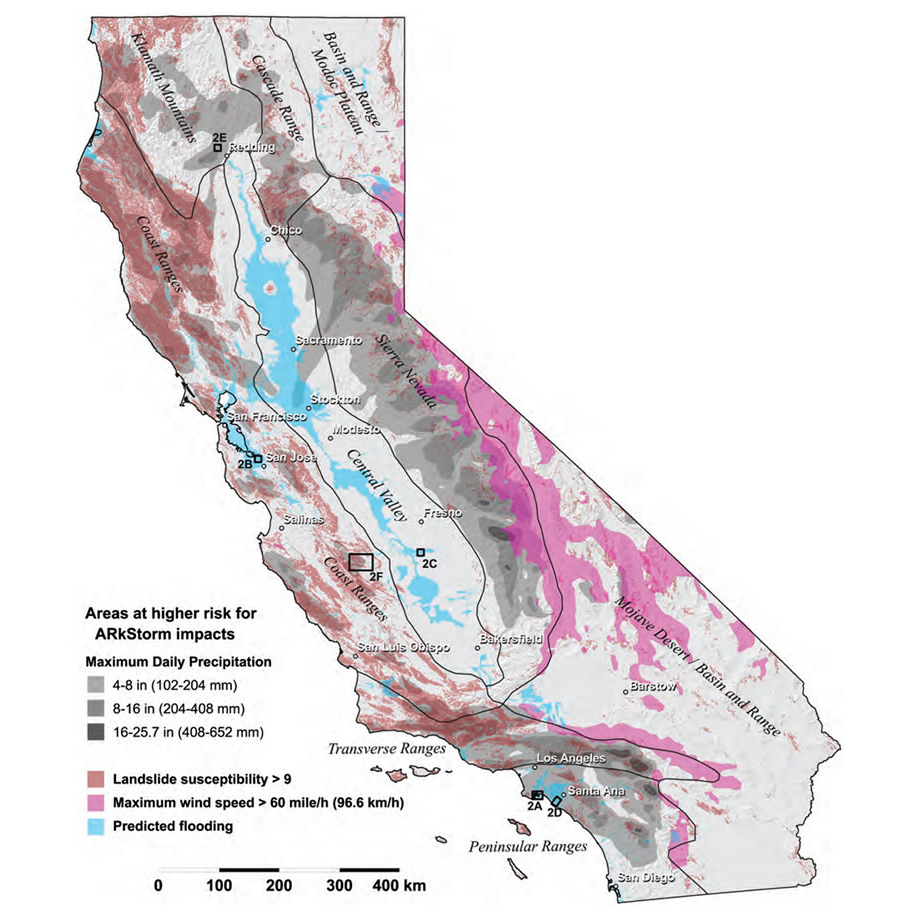

A USGS map shows ARkStorm predictions for California.

A USGS map shows ARkStorm predictions for California.

Swain pointed to Butte County as a region already hard hit by both sides of the hydroclimatic spectrum and a preview of events to come for the rest of the state. The county gained notoriety for the 2018 Camp Fire and two years later battled the North Complex Fire. The dam nearly burst in 2017 for Lake Oroville. Buffering the brief wet period were two extreme droughts that drove up prices for cattle feed for area ranchers and led to significant fallowing for rice growers. Northern California struggled this year under the rapid onset of drought after a near-average snowpack largely disappeared rather than replenish reservoirs.

“What's clear is that precipitation-only drought metrics are becoming increasingly misleading in a warming climate,” said Swain. “The same amount of rain and snow just doesn't go as far as it used to.”

He argued this should lead to a paradigm shift in how state leaders think about water management. It is already shifting the research focus on climate issues. Swain is part of a team exploring a research endeavor called ArkStorm 2.0.

A slew of state and federal experts assembled to develop the initial ARkStorm modeling scenario a decade ago. Patterned after the 1862 event, the research explored the theoretical scenario of a series of atmospheric rivers (the “AR” in ARkStorm) carrying as much precipitation as hurricanes and pummeling the West Coast over several weeks. Such an event would lead to an estimated $725 billion in damages and other economic losses. Thousands of acres of urban and agricultural land would flood, resulting in catastrophic disruptions to water supplies and the evacuation of 1.5 million people. It would affect all counties and all economic sectors.

The existing flood protection system—designed to preserve urban areas—would crumble. Levees built for storms occurring once every 75 years would face 500-year streamflows, which ARkStorm deems a much more realistic outcome in today’s changing climate.

ArkStorm 2.0 will build on climate research published since the original modeling.

“We're reimagining ARkStorm for the climate change era,” said Swain, “which, it turns out, greatly changes the magnitude of what is physically plausible.”

He hopes to release results on the initial atmospheric modeling early next year, thanks to financial support from the Yuba Water Agency and the Department of Water Resources (DWR).

Swain recognizes the climate has already shifted in California and is forcing the state to move beyond its 20th century policies and infrastructure. He warned that the future has already arrived for climate predictions made just 20 years ago.

In a panel discussion last week for the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC), Tim Ramirez, who serves on the Central Valley Flood Protection Board, agreed with Swain.

Don’t miss a beat! It’s easy to sign up for a FREE month of Agri-Pulse news! For the latest on what’s happening in Washington, D.C. and around the country in agriculture, just click here.

“We're designing things now based on old standards in a different regime,” said Ramirez. “And we're not ready for the new cycle that's coming.”

He offered the San Joaquin River as an example. Over the past century, the state has re-engineered the river to carry snowmelt in a controlled, deliberate fashion down to the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. It was not built to handle floods, he said. Ramirez pointed out that rivers actually need floods to maintain healthy ecosystems. He also pushed for more floodplain restoration to better handle extreme weather events, citing as an example the Yolo Bypass that spills flood flows onto rice farmland and winter waterfowl habitat.

UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain

UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain

Ellen Hanak, who directs PPIC’s Water Policy Center, said agricultural lands along rivers must make more room for overflow to save the communities that abut those waterways. This strategy requires money to incentivize landowners and create more bypasses, she explained, adding that the Sacramento Area Flood Control Agency has pioneered innovative financial agreements with neighboring farmers for this purpose.

DWR Director Karla Nemeth said the state must also account for human behavior in response to rising temperatures. She noted that farmers started planting earlier in the season this year with warmer weather presenting an opportunity to get crops in the ground sooner. This led to water diversions earlier in the year and less flow later for endangered species protection.

With impacts to agriculture from the pendulum swing of extreme floods and drought, Swain cautioned that not all farmers and ranchers will be affected equally. Water supplies will be broadly constrained by the increased variability while winter rains may come with only a week’s notice, meaning increased flexibility will be a top priority for agriculture.

He was optimistic, on the other hand, for the role of growers in flood-managed aquifer recharge, or Flood-MAR.

“Agriculture is going to play a big part in that,” he said. “We need to retool systems and rework state water rules and policies so that it's possible to do this in the first place.”

On-farm groundwater recharge offers a flexible way to manage flood flows that may come only once every 30 years in some places, he explained.

Ali Forsythe, who manages environmental planning and permitting for the Sites Project Authority, added that new infrastructure investments will support Flood-MAR as well. The Sites Reservoir, as one storage proposal, would capture up to a million acre-feet of excess flows from the Sacramento River and hold that water to release over time for strategic groundwater recharge. She added that this type of off-stream reservoir would also store water for environmental releases and for municipalities, along with agriculture.

“Climate change is going to challenge us in the future in ways that we never thought was possible in the past,” said Forsythe. “We need to meet that challenge with our own innovative ideas, partnerships and willingness to move beyond the combat discussions to how we all get better together.”

For more news, go to: www.Agri-Pulse.com